Exposing the emotive foundations of the Australian housing crisis

Cutting through endless journalistic analyses of housing affordability, the works of two Australian artists, Narelle Jubelin and Rosemary Laing come to my attention.

In a matte square photograph with rounded edges, the timber frame of a modern single-family dwelling is erected on a concrete slab of Kandos cement. It is 1977 and this is the first photograph in a plastic photo album. The family stands proudly around the construction equipment, coming together to get their hands dirty; to physically build their home on a cleared section of land high in the sparsely inhabited plains of the Central Tablelands of New South Wales, on ancestral Wiradjuri country. Adjacent to the home paddock is a newly planted pine forest, the bushy saplings lined up and poised for their profitable 30-year skyward growth. Years later, the photographs record the addition of a pool, surrounded by a resplendent herbaceous border, its deck providing a jaw-dropping view of the surrounding valley unimpeded by security fencing. Optimism and burgeoning housepride radiate from these family snaps.1

In stark contrast, in November 2023, the Australian financial journalist Alan Kohler penned an explosive analytical piece for the Quarterly Essay titled The Great Divide: Australia’s Housing Mess and How to Fix It, pointing out the concatenation of political and economic factors that have placed the dream of home ownership farther out of financial reach of the youngest generations of Australians; the value of housing far outpacing income growth since the turn of the millennium. “The fact that one of the least populated countries on earth contains the world’s second most expensive housing is a national calamity and a stunning failure of public policy” he wrote.2 Even more recently, an infographic shared on the social media channels of the Australian Broadcasting Company estimated an average annual income of $293,578 was required to afford a house without financial stress in my hometown of Sydney [according to the ABS, average weekly earnings for employees in November 2023 was $1888, annualised to $98,176]. 3 The cost of a new build, quite apart from the unavailability of undeveloped land in capital cities, is similarly exorbitant.

Cutting through this miasma of housing affordability crises unravelling in every tab open on my computer, the works of two Australian artists come to my attention. Fittingly exhibited in local galleries, their works treat themes of the home, housing, safety and security, reflecting the financial, social and ecological concerns woven into the act of building shelter. Created in the first decade of the 2000s, these works were already exploring the environmental and political complexities of land settlement and urban sprawl, interwoven with the emotional resonance of family memories and hopes for future generations.

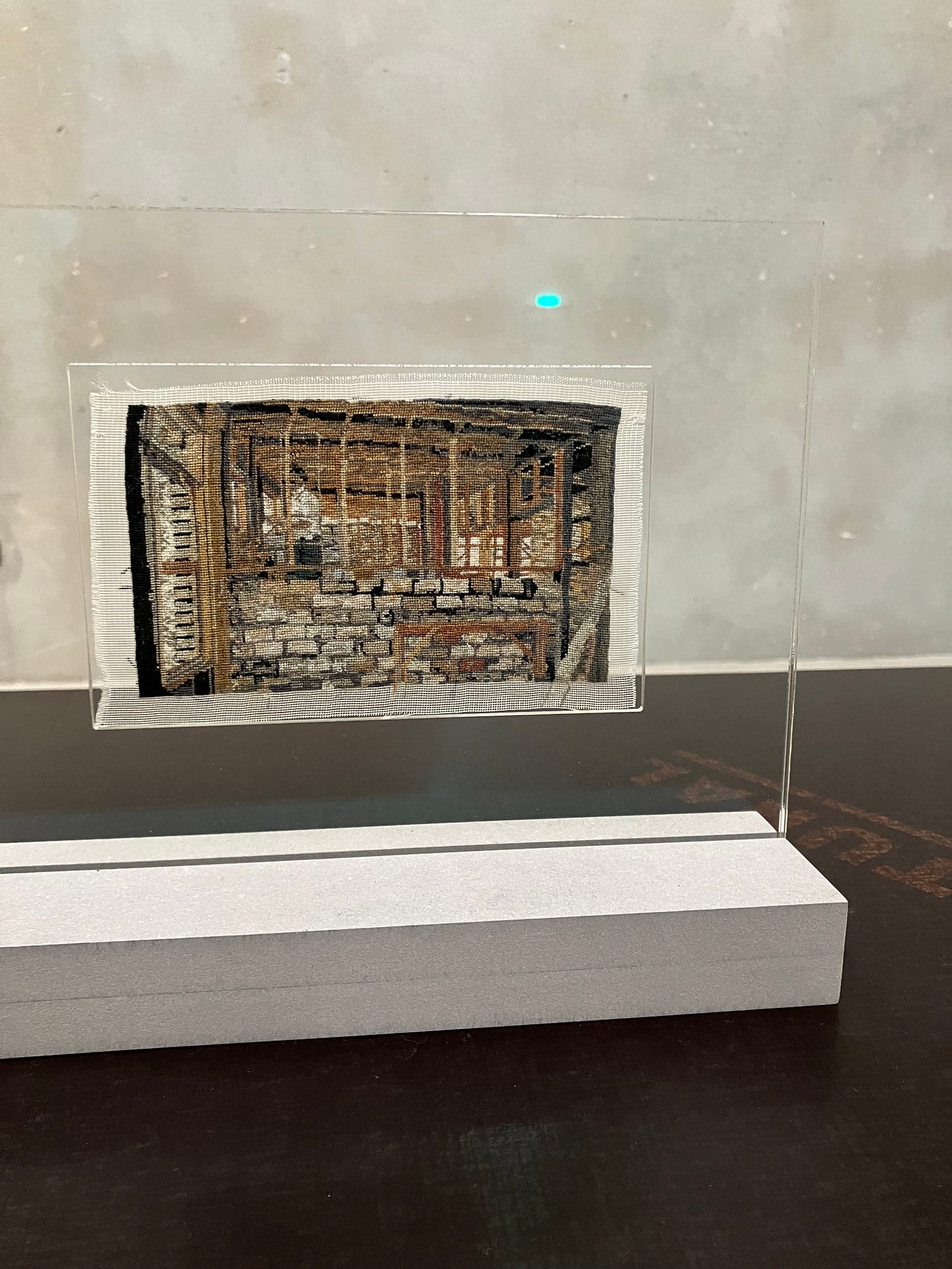

Shown in a solo exhibition, Contexto: For RDJ, RG and TH, at The Commercial in Marrickville, is a suite of works by Narelle Jubelin, who has lived and worked in Madrid since 1996. Painstakingly reproducing in petit-point embroidery her father’s photographs recording the construction of the family’s home on a block of land on Dharug country in 1964, Jublin’s series Owner Builder of Modern California House was first started in 2001. Including two vignettes created in 2024, Owner Builder has now grown to eleven separate images. The shape of a rectilinear structure of a modern single-family dwelling rises incongruously from a dry expanse of bush, what was at the time a newly established suburb of Sydney, surrounded by distinctive grey-green eucalypts. Revisiting these photographs with both temporal and geographical distance, Jubelin sits with the memories of her childhood home, rebuilding the structure herself in a new medium. Stitched through silk mesh, the slow, dextrous labour of needlecraft stymies the rapid progress of the building’s edification, taking form in a storyboard progression of successive images.

The permanence and solidity of the house’s architectural structure are fundamentally at odds with the delicate and intimate portability of Jubelin’s finished works, which are separate from and no longer physically tethered to the land. The works are currently exhibited in double-sided glass cases, which expose the raw white edges of the silk mesh, gently undulating in a hermetic bubble, its knotted reverse also visible. In a cavernous concrete warehouse conversion, the works are lined in a row on a table, with chairs kindly provided for the crouched, close-up viewing required of these small-scale needlepoints. As Amelia Wallin noted in her essay accompanying the exhibition, the California struck through in the title of this work points to the ubiquity of Modernist housing in the Western world, and in removing the geographical markers of her works, Jubelin enables her audiences to project their own family histories in their readings of her work. Jublelin created these works while travelling between Sydney, Madrid and Los Angeles, returning to them over 20 years of practice, while her elderly parents continued to inhabit the house that still stands.

Meanwhile, a disorienting panoramic photograph of a houseframe upturned on a hill dominates Annette Larkin’s gallery space across town. An image from Rosemary Laing’s 2010 project, leak, this cinematic photograph, Jim4, depicts a half-constructed single-family suburban house in the deserted, pastoral Cooma-Monaro district of New South Wales. Under the misty skies of a storm, the house’s blond timber frame is backlit and uniquely glowing amongst the gums in which it is embedded. Alone in the rugged landscape, the house’s wooden frame has landed upside-down within this grove. The apex of its gabled roof is buried in the ground - as if the house had been lifted and deposited haphazardly in the landscape by unseen malevolent forces.

Laing has rectified our view of this house by flipping the entire landscape image, putting skies below and the Antipodean landmass fittingly clinging to the uppermost edge of the image. Invading the landscape, yet frustratingly unable to be fully completed and utilised, this house was built specifically in situ for this project. It stands anonymously as a metaphor for the unnatural disturbance and the environmental destruction wrought on the environment by modern housing. Echoing Jubelin’s decontextualisation, the raw state of this structure allows for a wide geographical reading of the strangling creep of suburbia. Although Laing refuses “sentimental nostalgia for a mythic and undespoiled past”5 , the artist displays a bleak view of the environmental implications of continuing land settlement and the cultural transformation of the landscape in these contested lands. The optimism of photographic building progress reports is gone, and in its place lingers an end-of-days eerieness, the environment gathering its might to reject the invasive foreign presence.

Forty years later, this home, a cherished meeting place for four generations of an Australian family, would be razed in the 2019-2020 ‘Black Summer’ bushfires, leaving standing only a burnt-out Landcruiser and a bunk-house shed.

Alan Kohler, The Great Divide: Australia’s Housing Mess and How to Fix It: Quarterly Essay 92, Black Inc., Melbourne, 27 November 2032. (second only to Hong Kong)

Based on analysis by the Parliamentary Library, based on data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics and Core Logic, 27 March 2023 [https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/earnings-and-working-conditions/employee-earnings/latest-release]

Drawing on the region’s rich cultural history, Liang has given the images in this series character’s names from Patrick White’s 1979 novel The Twyborn Affair, set in the Monaro.

Abigail Solomon - Godeau, Rosemary Laing, Piper Press, Sydney, 2012, p. 35