Review: Sprague, Q., Ken Whisson: Painting & Drawing, Drill Hall Gallery Publishing and The Miegunyah Press, Canberra/Melbourne, 2023

I got my hands on an early copy of the new monograph on Ken Whisson - a sumptuous publication and a great addition to the reference art library!

Ken Whisson’s sudden death in Sydney in February last year at the age of 94 took the art world by surprise, brutally curtailing the seemingly unstoppable practice of one of Australia’s most consistent and idiosyncratic painters. The sparsely furnished Elizabeth Bay apartment, where Whisson had lived ascetically since his return from decades of expatriate Italian living in late 2014, contained half a dozen paintings yet to be finished, canvases turned to face the wall awaiting final revisions, and sheaves of ink-on-paper drawings. What Whisson’s untimely demise also rudely interrupted was a continuous dialogue with Quentin Sprague, curator and academic, who, since April 2021 had taken to visiting and calling on the phone the artist to carefully record his memories and explanations of his practice. Writing last year, Sprague described Whisson’s paintings as “hard and uncompromising, but full of light”.1 Indeed, Whisson’s paintings all presented cryptic meandering journeys through time and space, teetering through fragmented visual imagery real, remembered, and imagined, his incessant creative drive sustained by a remarkable “focus on intuition as a guiding principle”.2

Including the piles of slim, illustrated solo-exhibition catalogues from Niagara Galleries, Melbourne, and Watters Galleries, Sydney, almost all previous monographs of Ken Whisson were published to accompany solo survey exhibitions. The most recent and extensive of these was Glenn Barkley and Lesley Harding’s encyclopedic catalogue of 200 paintings and drawings, As If, produced for Whisson’s major retrospective at Heide Museum of Modern Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art, in 2012. Works on paper were given equal investment and focus throughout this exhibition and catalogue, interspersed throughout the text and with all works illustrated at the back of the catalogue in chronological order. Ten years before this, in 2001, Whisson’s representative gallery in Melbourne had published a handsome hardback volume covering (only) his paintings of the last fifty years 1947 - 1999, accompanied by an essay written by John McDonald and an important selection of reprinted writings and talks by the artist between 1969 - 1999. As far as I can tell, this is the only publication that features these full, unedited texts, although many, including Sprague’s new book, reprint multiple tracts of quoted text from these talks. Ken Whisson. Paintings & Drawings is, in fact, book-ended by analyses of two of the artist’s lectures; starting with one given in 1994 at the Ballarat School of Art (which had been reprinted in full in the Niagara Galleries book) and culminating with his last public appearance, a talk given to students at the National Art School in September 2015, returning to the same questions of how to sustain originality in one’s creative practice.

Sprague’s book, in contrast to previous monographs, illustrates in individual plates 136 paintings and 107 drawings grouped into three geographical-chronological chapters: 1940 - 1977 Melbourne; 1978 - 2014 Perugia; 2015 - 2022 Sydney. These plates follow a detailed and easily readable biographical prose of almost a hundred pages, divided into seven thematic chapters, with judicious ekphrasis on major works. The plates are not always printed in chronological order. Occasionally the linear order of pictures is amended to provide a more fitting conceptual flow - for example, the last painting illustrated is Arrival Point of Many Drawings, 2021, leading neatly into the sequence of illustrated works on paper; and repositioning the later 2022 painting Animals, Birds and Grass to the penultimate plate. Unfortunately, although asserting the central importance of drawings in Whisson’s practice at several points throughout the prose, both in Sprague’s own words and in interpreting (sometimes contradicting) the artist’s writings, the illustrations for works on paper are reproduced in isolation from the paintings, obscuring the rich dialogue and dependence between these two material branches of the artist’s practice. It is worth noting here that both Watters Gallery and Niagara Galleries routinely included a significant number of works on paper within each of Ken Whisson’s almost annual solo exhibitions.

Whisson has often been described as an “artist’s artist”, a respectful epithet for a creator of works resisting mass appeal. Sprague disagrees with this “well-intentioned but ultimately misguided” 3 assessment, arguing that by the end of the 1970s, Whisson had attained a greater period of accessibility, with art sales finally providing a reliable stream of income. John McDonald in his obituary of the artist likewise qualified the works produced on Whisson’s return to Australia in the 1970s as a “purple patch”4. My experience in the secondary art market in Australia, where Whisson paintings were regularly traded, also seems to support this identification of the early 70s as the height of Whisson’s appeal [paintings from 1973-1980 featuring St Kilda, Flags, and Car subjects account for the several of the highest prices at auction to date, with total prices all above $55,000 and indicative of broad market interest]. I nevertheless believe that Whisson’s work is deeply admired by but a small, devoted, coterie of collectors.

During his lifetime, Whisson did not seek fame or pandy to commercial tastes, preferring to seek what he called “a public of individuals”, founded on the idea that the “relation of art is of individual to individual”5. There is a truism in the Australian art dealing business that if you are an owner of one Ken Whisson work, you are generally likely to own many. This is confirmed by the recurrence of habitual names of private collectors whose Whisson works were reproduced in this publication (and in the previous monographs): James and Jacqui Erskine, Martin Gascoigne and Mary Eagle, Clinton Tweedie, Rob and Carole Andrew, Laverty Collection and Hassall/Milson Collection, these latter having provided crucial support to the publication of this book. It is also true to say that Whisson was an artist’s artist, particularly in consideration of the support provided by fellow artists and other influential cultural stalwarts in establishing his secure presence in the Australian art world.

While Ken Whisson was mostly self-taught, his early social interactions, facilitated through family involvement in the literary community of Melbourne, with first-wave Australian Modernists (such as Sidney Nolan, Albert Tucker and Joy Hester) left indelible imprints on the development of his visual language. These interactions are intricately related in Sprague’s text, including recent revelations by Whisson about specific artistic influences drawn from this period in the 1940s. Sprague has identified and reproduced the exact drawing by Joy Hester from the 5th issue of Angry Penguins in 1943, which in Whisson’s words provided “'the entire inspiration for all my drawings since”6. Whisson had also spoken to Joe Frost in 2016 of being “struck forcibly” by this drawing, although the work in question was not named nor reproduced in the illustrations accompanying Frost’s article in the review Artist Profile7. Sprague goes one step further in his unparalleled archival research, finding evidence of the artist’s first real-life interaction with Hester’s artwork in 2011, buried in Whisson’s epistolary correspondence within his artist’s dossier at the British Museum.

Crucial to Sprague’s understanding of the first five decades of Whisson’s life was the interview of the artist conducted by artist/writer Barbara Blackman in April 1984 under the auspices of the National Library of Australia Oral History Programme (one of almost 150 interviews conducted by Blackman for the NLA). Sprague’s analysis of the reciprocal appreciation and similar approaches in artmaking between Whisson and fellow artist Rosalie Gascoigne is particularly insightful. The author’s accounts of their interactions over many years are bolstered by present-day interviews with Gascoigne’s son Martin Gascoigne, cross-referenced with letters between the artists and eminent curator Jim Mollison (friend and supporter of both artists), and finally of Martin Gascoigne’s stellar, exhaustive catalogue raisonné of his mother’s oeuvre, published by ANU Press in 2019. The positive influence of other Australian artists in Ken Whisson’s life extended right through to his final days, with Sydney-based painters Joe Frost, Sue Soliman, and Henry Mulholland providing regular visits and assisting the artist in running errands which had become difficult in his old age.8

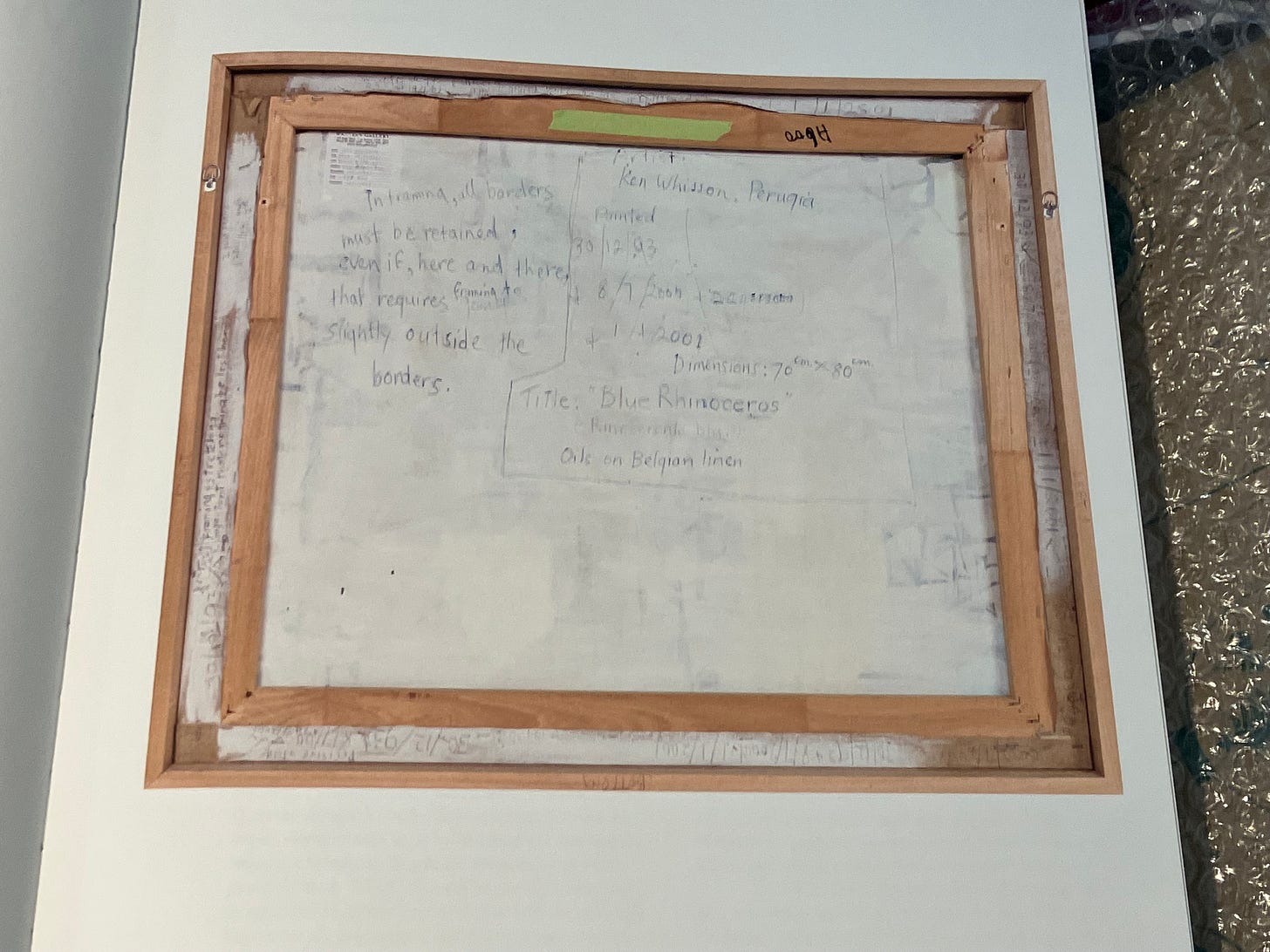

Quentin Sprague sets the tone for his book - an engaging and exhaustive publication for the converted, with a focus on the act of creation - from the very first pages: the table of contents and its accompanying illustration in pride-of-place on the left-hand page. This illustration is not of a painting, but of the reverse of a framed painting, The Blue Rhinoceros, 2001 (Hassall/Milson Collection). Wisely illustrating its front on the following page (in an interesting reversal of the traditional method of picture-viewing), Sprague first appeals to the art curators, historians, archivists, and presumably a handful of curious art lovers in using this secret view to provide additional insight into the artist’s creative process. Although it is a widely adopted convention in auction houses to provide “verso photographs” in online catalogues, it is vanishingly rare to see them published in print. The extensive dates and inscriptions on the back of this work will not surprise those already familiar with Whisson’s work, however, it is a shame that this is the only instance in the book where this is shown.

Dense with information drawn from a broad range of first-person interviews, and extensive archival research, Ken Whisson: Paintings and Drawings is a hugely valuable academic resource, which falls just short of being a true catalogue raisonné. This is likely an astute and conscious choice by Sprague, considering Whisson’s prolific output, purportedly exhibiting only 6 or 7 of every 100 paintings created annually! 9 It is a pleasure to have been provided with such a wealth of information on one artist, with Sprague chasing with equal interest various threads of inquiry - from Whisson’s obscure titular literary references to reproducing in facsimile various pages of the artist’s hand-written notebooks [one relatable sentence from 2011-2012 reads, in Italian, “why do I have such difficulty in remembering Daniel Thomas’ name?”]. Terence Maloon has quite appropriately written in his foreword “Sprague makes perfect sense of Whisson’s life and art, being able to read one in terms of the other”.10

Sprague, Q., ‘Ken Whisson: A Life Made in Art”, The Monthly, Schwartz Publishing, Melbourne, 7 March 2022

Sprague, Q., “1. Intuition and Memory”, Ken Whisson: Paintings and Drawings, Drill Hall Gallery Publishing and The Miegunyah Press, 2023, p. 6

Sprague, Q., ibid, p. 68

McDonald, J., ‘Ken Whisson: artist with no desire to follow the rules’, Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, 3 May 2022

“Talk 1985 - ‘The Possibilities for Communication in a World of Mass-Communication Systems’”, Canberra Art School, late 1985, in Ken Whisson. Paintings 1947 - 1999, Niagara Publishing, Melbourne, 2001, p. 139

Ken Whisson, interview with Quentin Sprague, 1 April 2021

Frost, J., ‘Joy Hester - A recollection by Ken Whisson’, Artist Profile, Sydney, Issue 34, March 2016, p. 118

Sprague, Q., Ken Whisson: Chronology, ibid, p. 483

Terence Maloon, Foreword, in Sprague, Q., ibid, p. 2

Ibid, p. 1