Louise Bourgeois - Archival Memory Banks and Personal Dénouements

Thoughts ahead of "Louise Bourgeois: Has The Night Invaded the Day or Has the Day Invaded the Night?", Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 25 November 2023 – 28 April 2024

First hinted at in March 2019, with a certain pre-pandemic optimism in transnational cooperation and public programming, to a sold-out theatre of art-inclined Sydneysiders, the “very special something”1 solo exhibition of the late Franco-American artist Louise Bourgeois will be opened at the Art Gallery of New South Wales on the 25th of November. Alongside a concurrent exhibition of works by Vasili Kandinsky, Has The Day Invaded the Night or Has the Night Invaded the Day? is Sydney’s summer blockbuster show, presented by the Sydney International Art Series.

Only receiving widespread international acclaim and popularity in old age, despite over seven decades of almost continuous artistic practice within some of the most important crucibles of Modern and Contemporary art, Bourgeois has now become a cult figure and a household name. International scholarship, stimulated and funded by the Easton Foundation (the non-for-profit dedicated to the preservation of the artist’s legacy and sustaining continued research through the establishment of the Louise Bourgeois Archive), has recently been reevaluating the central role of writing within the artist’s extensive oeuvre, removing unhelpful boundaries between her plastic works and those written in her diaries2.

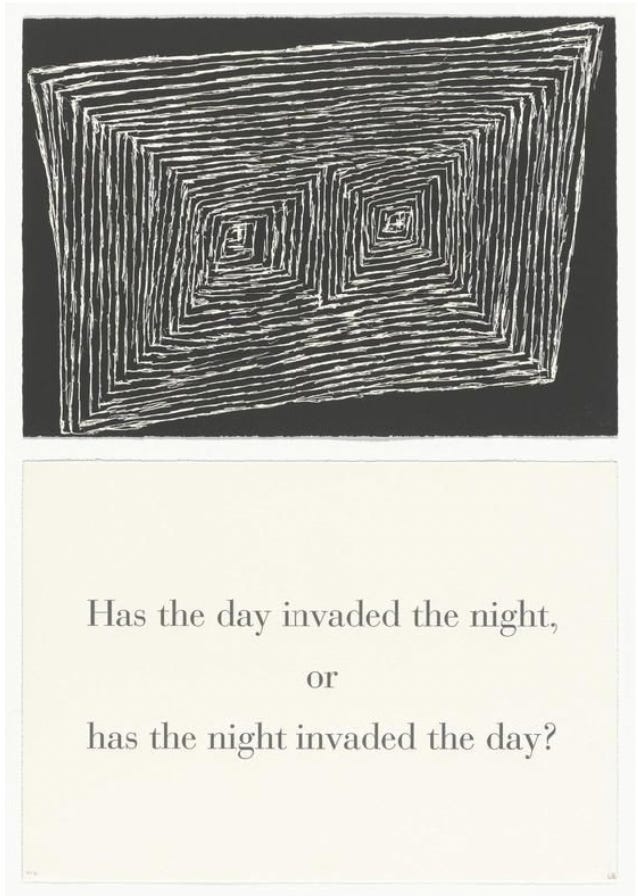

The long-winded title of this forthcoming exhibition “Has the Day Invaded the Night or the Night Invaded the Day” we are told was taken from one of the artist’s diary entries from the 1990s. The phrase was then lifted from the diaries by the artist and explored in her printmaking series What is the Shape of This Problem, 1999.

The gouged jagged spiral form printed to accompany this text could remind Australian audiences of the dizzying concentric topographical patterns of sacred landscapes in Pintupi art, for example in the works of Warlimpirringa Tjapaltjarri. Louise Bourgeois was fond of the spiral form, relating it to the act of wringing out dyed fabrics in her childhood: ‘The spiral - I love the spiral - represents control and freedom’, she wrote in 1994.3 Often described as the “inventor” of the confessional art, Bourgeois is famous for weaving autobiographical content into her art. With introspective curiosity she mined her memory bank and used psychoanalysis to tap into the unconscious, finding subject matter to translate into artworks in a wide range of media; works that evoke the most emotive and visceral of responses in the viewer.

In creating something broadly relatable out of deeply personal subject matter Bourgeois’ artworks elicit, in kind, a subjective response - an intellectual and affective call-and-response. Even the most recently published biography of the artist, a novella from 2018 written by Jean Frémon, long-term friend and Parisian dealer of her work, was described by the London Review of Books as “more like a portrait painting”, creatively and posthumously written from the perspective of the young artist. 4

I attended the first lecture of the Learning Curve series presented at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in conjunction with the awaited exhibition, a few weeks before it opened. Within assistant curator Emily Sullivan’s didactic presentation, she too, was tempted to relate her own personal stories of hoarded heirloom textiles and childhood cubby houses, drawing parallels with Bourgeois’ repurposed mementos and the childlike structures that permeate her sculptural works. In anticipation of this solo exhibition, the first to be held in Australia, I find myself thrown into an introspective trip through my own memories and paperasses. I try to reconstruct my past experiences with Bourgeois’ artworks, applying a retroactive ordering action to my personal images and written thoughts scribbled on bits of paper, thoughts that have evolved while the artworks themselves have remained the same. Having moved overseas like Bourgeois, I too have been followed by a bindle of personal archives. Although I acknowledge the grandiosity of calling my boxes of scribbled feuilles and mistitled JPEGs in external hard drives an archive, it still nonetheless imbued what Derrida qualified as “the authority of beginnings”.5 What we chose to collect becomes a clear reflection of our values and identity, reinforcing belief systems and ultimately engendering a self-fulfilling prophecy.

My personal reflection begins with Taschen anthology, Story of Women Artists, published in 2005 which I received the same year, well before the role of female artists had become a real topic of critical and institutional re-evaluation. For context, the Art Gallery of New South Wales only formally amended its acquisition policy to prioritise the collection of women artists ten years later, in 2015.6 Within this book, Louise Bourgeois rightfully features, illustrated with a full-page image of her iconic arachnid sculpture Maman, 1999, installed in its first presentation, the inaugural commission of the Unilever Series at the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern in London when it opened in 2000. The other works in this commission were a site-specific tripartite installation of steel towers, called I Do, I Undo and, I Redo, 2000.

Two years later, with the privilege of visiting European family during the holidays between my last two years of high school, I saw Maman in real life, installed in front of the same Tate Modern gallery for the first presentation of a major touring retrospective of Louise Bourgeois’ work, one of the last during her lifetime. I take a photo leaning over the glass balcony of the fourth floor of the museum, looking down in the cold January air over the 9m high sculpture.

Eight days later a press release announced the acquisition of this sculpture for the Tate’s permanent collection, “a gift of the artist and an anonymous benefactor” - a timely change in ownership before she was shipped overseas to the other satellite museums of this touring show: Pompidou, Guggenheim, LACMA, and Hirshhorn. While this Maman from 1999 is Bourgeois’ original sculpture made of steel, bronze and marble (used for the white eggs suspended within a wire mesh sac beneath the arthropod’s abdomen), the artist later chose to cast her sculpture in bronze in an edition of six, with the expert assistance of Modern Art Foundry, in Queens.7 Proliferating in prominent art museums around the world much like Yayoi Kusama’s (much lighter) fiberglass pumpkins, this battalion of bronze spider mamans become accessible symbolic effigies of the artist, permanently installed in Ottowa (National Gallery of Canada), Bilbao (Guggenheim), Tokyo (Mori Art Gallery), Bentonville, Arkansas (Crystal Bridges Art Museum) and Doha (Qatar National Convention Centre). In my 2008 photo, taken with a Sony Cybershot digital camera, the original Maman stands on pointed tippytoes, craning up on sinewy muscles, her legs twisted into spirals as rugged-up tourists and city flaneurs stroll beneath her. 8

Alongside my own, french-speaking maman, we rendezvous with two of my paternal English aunts to see the exhibition. Reflecting back on that day, the 3 January 2008, with a greater (but still incomplete) understanding of the deep currents of child abuse that existed in the most recent generations of my father’s family, it seems like an astoundingly brave choice of meeting place and activity. Faced with a sequence of sculptural installations, Bourgeois’ famous Cells, vast rooms encased with penitentiary chickenwire, eerily filled with menacing objects and uncanny stuffed figurines, let alone a work in which the artist explicitly fantasises about patricide9, my triggered English aunts made a premature exit. The reasons for this abrupt and emotional departure I could only chalk up at the time to the general atmosphere of the works and exhibition, which I noted in my earnest hand-written report later in the hotel, as “gothic”, “shocking” and “disturbing”. I had yet to reconcile this experience with the figure of my ostracised paternal grandfather, whom my mother and I had visited earlier during that same trip. With the geographical and chronological distance, it seems fitting that at the same time, Colombian artist Doris Salcedo’s Shibboleth was physically cracking the floor of the Turbine Hall with the metaphorical weight of division.

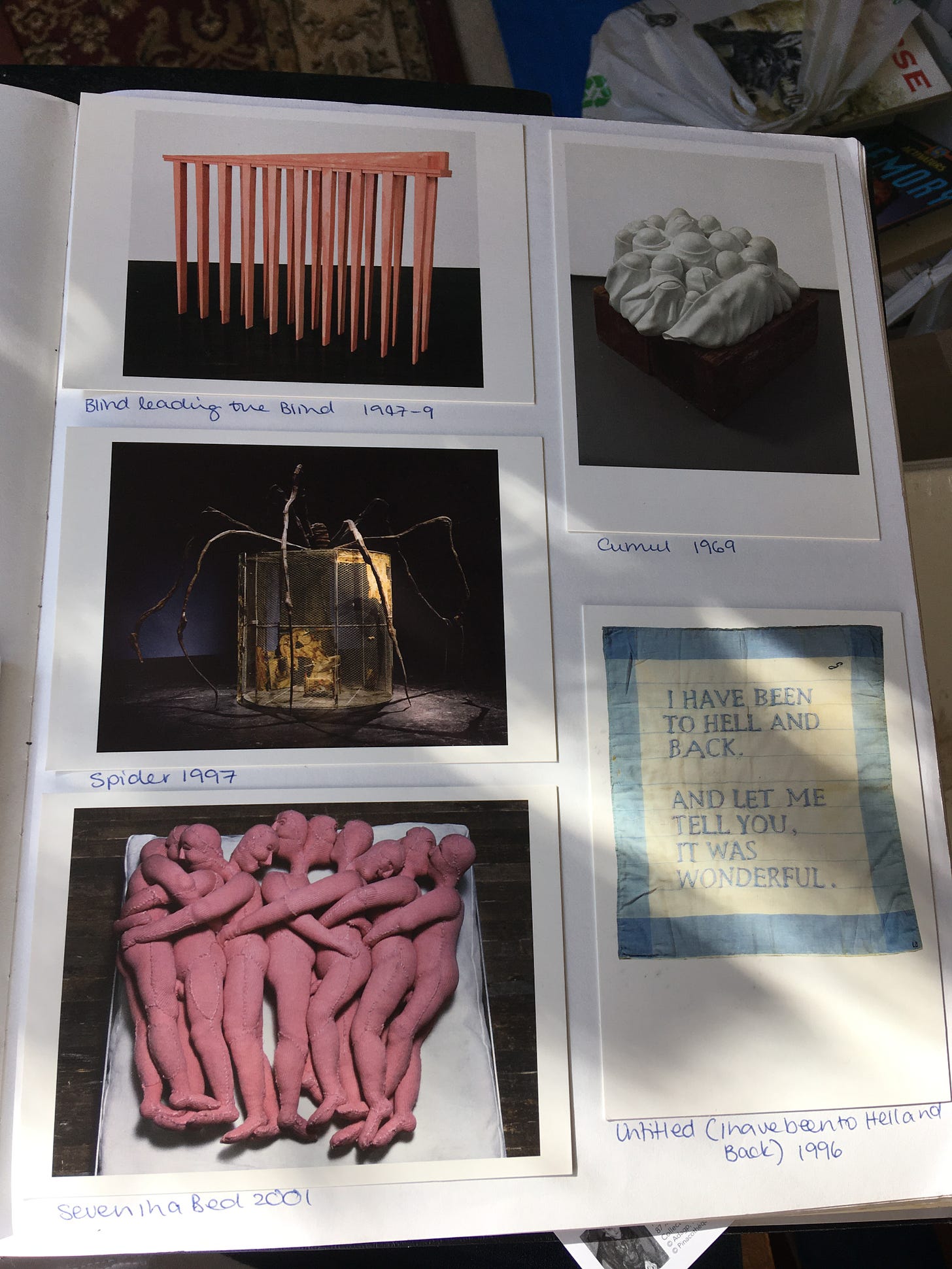

Back in 2023, the first lecture of a Louise Bourgeois-themed Learning Curve series revealed a preview of a handful of the artworks to be included in the exhibition, several of these were linked, de fil en aiguille, through the common theme of sewing and the act of reparation: the Needle Woman totemic personage of 1947-49, the suspended nest structure Fée Couturière, 1963 (cast 2010) based on the nest of the common Asian tailor bird, the artist’s book of digitally printed and screen printed fabrics, Ode à La Bièvre, 2007 and a pair of stuffed fabric figures: Couple, 2001, which will be exhibited suspended in space in the underground Tank in the new North building. Much has been written about Louise’s familial connection to sewing, her parents having run an Aubusson and Gobelins tapestry restoration business just outside Paris during the Third French Republic. It was only in the 1990s however, that Bourgeois began to repurpose familial textiles as a support and subject of her artworks. She created crude puppet-like figures and stuffed heads and took to embroidering and screenprinting witty aphorisms and confessional texts onto hankies. Two of these fabric works exhibited in the Tate retrospective featured on postcards that I duly pasted into my Year 11 art workbook (photo): the writhing janus-headed figures of Seven in a Bed, 2001 and a ladies’ hanky Untitled, 1996, neatly emblazoned with the words in capitals, “I HAVE BEEN TO HELL AND BACK. / AND LET ME TELL YOU, IT WAS WONDERFUL”. The links to contemporaneous Young British Artists working in fabric, especially Tracey Emin, had not been lost on me at the time. Emin herself wryly commented: “I have to be really careful not to make work that looked like Louise Bourgeois’, because it would be just so easy for me. But also, I have to remember that Louise Bourgeois doesn’t have carte blanche on dangly, sewn things”. 10

Emin, however, was much younger than Louise in the 1990s, and the purposeful handmade quality and crude stitching of her works served to portray a girlish innocence, whereas Bourgeois’ adoption of fabric works aged well into her 80s encapsulated a geriatric regression into childhood habits, the maladroit crudeness of stitching and fragility of her aged fabrics (both real wear-and-tear and that which the artist created by facsimile) echoing her own physical decline. 11 The history of textiles is a female one. Until cheap polystyrene textiles proliferated in the 20th century, heirloom cloths, particularly household drapery, were carefully looked after and constituted a large part of a bride’s trousseau. Today it is not unusual for millennial women such as myself to not own even one tablecloth, as my mother recently discovered and swiftly set about finding me one to inherit from my grandmother’s estate. By reappropriating household textiles, tangible reminders of her own personal history and iconography, into subversive artworks that question her role as a mother and daughter in a foreign land, Bourgeois reinforces her position as an artist, first and foremost.

Bourgeois’ artwork was profoundly shaped by her migrant experience, in particular by a sense of guilt at having left behind family and specific locations of sentimental importance and finding comfort in the material possessions that she had retained. Her upright Personnage figures from the 1940s were stand-ins for a familiar social entourage she no longer had, suffering cultural displacement after having recently moved to the United States with her husband, Jewish art historian Robert Goldwater. 12 Like these and the upright pilotis of Bourgeois’ Blind Leading the Blind, 1947 - 1949, another work that featured in my pasted-in postcards, I had once trudged through the Tate retrospective, attempting to understand the affective nuances of guilt, terror, and defiant self-assertion, notions which were only beginning to form in my adolescent mind.

Based on the 1568 painting by Peter Breughel the Elder, The Blind Leading the Blind is Bourgeois’s best-known early work. A rectilinear assemblage of found timber beams yoked together under a lintel into a single multi-legged headless structure, taller than a man, it appears to advance in bilateral coordination, a gait reminiscent of that of a centipede. It speaks to a feeling of devotional or oppressive powerlessness and disenfranchisement. Bourgeois returned to this 1947 composition several times, painting three of the five variations in a coral-pink hue. Speaking at the same March 2019 gathering, Jerry Gorovoy, Bourgeois’ last devoted studio manager, explained how these were painted pink in the 1970s “as a feminist gesture”. Gorovoy, in a serendipitous coincidence, had been the young curator of a group exhibition Ten Abstract Sculptures in March 1980 at Australian Max Hutchinson’s gallery in New York City, from which James Mollison purchased C.O.Y.O.T.E., 1947-1949, for the nascent Australian national collection - a key sculpture presumably to be included in the forthcoming exhibition on loan from the National Gallery of Australia.

By the time I finish writing this essay, the installation of the exhibition Has The Night Invaded the Day…Or Has the Day Invaded the Night is almost complete. Anticipating the opening of the exhibition at the end of the week, I follow with interest the “unboxing” experience of sequential photos posted on Instagram of Maman being installed on the forecourt of the gallery’s South Building. Head of International Art, Justin Paton posts an ephemeral story of the first set of four legs being placed, while artist Wendy Sharpe gushes in all caps about the enormity of the sculpture as it is being installed on the 14th of November, posting a series of photos of the acephalic sculpture surrounded by men in visi-vests and enclosed in temporary orange plastic waterfilled and steel topped barriers. Bearing strong resemblance to Bourgeois’ own gated and grated Cell constructions, I almost wish this pragmatic enclosure could remain in place throughout the exhibition. I wonder if Maman will now feel smaller to me, dwarfed by the neo-classical sandstone colonnade of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and the two allegorical bronze statutes: The Offerings of Peace and The Offerings of War, by Gilbert Bayes, which have stood sentinel on the forecourt for almost one hundred years.

Maud Page, Deputy Director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, during a lecture “Life & Art with Louise Bourgeois”, on Saturday 2 March 2019

see: Word & Image: Louise Bourgeois, Through the Archives, Taylor & Francis, Vol. 38, Issue 1, 2022

The artist cited in Louise Bourgeois, Paul Gardner, New York, 1994

Greer, R., ‘Now Now Louison’, London Review of Books, 2018 [https://thelondonmagazine.org/review-now-now-louison-by-jean-fremon/]

Steedman, C., ‘Something called a fever: Michelet, Derrida, and Dust”, American Historical Review, issue 106, no. 4, 2001, p.1159

Brand, M., foreword, Here We Are, exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2019

Manchester, E., Louise Bourgeois - Maman, 1999, Tate, 2009 [https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/bourgeois-maman-t12625] ; Gates Anderson, N., ‘Where Bronze Transforms into Fine Art’, New York Times, 6 September 2012

Although convincingly realistic, spiders do not have extensor muscles in their limbs, controlling them instead by hydraulic pressure - which is why one finds dead spiders with their limbs symmetrically folded inwards.

The Destruction of the Father, 1974, Bourgeois’ claustrophobic first installation recreating a family dinner at the table, enacted with plastic and latex pustules.

Tracey Emin, interview with Jean Wainwright, undated, published in Merck, M, and Townsend, C. (eds), The Art of Tracey Emin, Thames and Hudson, London

Linda Nochlin, ‘Old-Age Style: Late Louise Bourgeois’ in Louise Bourgeois, Tate, p. 190

Josef Helfenstein, ‘Personages: Animism versus Modernist Sculpture’, in Louise Bourgeois, Tate, pp. 207 - 209