LESLEY DUMBRELL - THRUM

Australian Op-Art hypnotic painter finally gets her due at the age of 82

“But now is the time that sexuality should be revalued within abstract painting modes to save it from the art-for-arts’-sake vacuum into which it has been drawn”1

Lesley Dumbrell, having cultivated a career as a practising artist of hard-edge abstraction for over five decades, is fortunate to see her artworks gathered together in a retrospective survey exhibition at a large state institution: Thrum, Art Gallery of New South Wales. Thanks to overt curatorial programming seeking to redress historical imbalances in gender representation, Dumbrell is awarded this long overdue accolade, complete with a large scholarly catalogue and associated events fostering engagement with young contemporary artists. Many overlooked female artists, if they receive this accolade at all, do not live long enough to experience it and as the artist herself puts it, hope to “see what I learn from it”. 2

Although Dumbrell was firmly based in Melbourne throughout the 1960s - 1990s and today lives and works in Bangkok, she had a crucial early presence in the art worlds of metropolitan Brisbane and Sydney. By the time the Art Gallery of New South Wales was purchasing Spangle in 1979 ahead of Dumbrell’s first solo exhibition at Sydney’s Gallery A in 1980, her work was already represented in the collections of the Australian National Gallery (today the NGA), the Queensland Art Gallery (today QAGoMA) and the National Gallery of Victoria. In recent years the Art Gallery of New South Wales has significantly increased the number of works by Dumbrell in their permanent collection, particularly acquiring the preparatory studies for existing paintings in their collection to be displayed together in this current exhibition. The artist played an active role in the presentation of this exhibition - she was seen supervising the installation and was present to participate in associated panel discussions in Sydney and Melbourne.

Reuniting a life’s work in a retrospective exhibition or a publication such as a catalogue raisonné can be misleading in that “it lends a significance to continuity that does not reflect the conditions in which the work was brought about in the first place”.3 It also provides a chance to rectify and re-evaluate historical roles, to retrace influences that had not previously been obvious. By her own account, the artist had been disadvantaged by the various indignities of being a woman artist (for example, changing her name through marriage resulted in an inconsistent presence in the industry and press).4 However, today she is celebrated for her galvanising presence amongst a community of practising female artists in Melbourne throughout the 70s and 80s. Dumbrell, inspired by the visiting great US feminist Lucy Lippard, founded the Women’s Art Register and the Women’s Art Movement, providing an active community to support female art practice beyond marriage, thus defying the unambitious expectations of her former teachers. This exposure led her to be described in the press as a ‘militant’ and ‘marvellously self-confident without being shrill’.5 Thankfully, Dumbrell’s work was supported by key and influential commercial female gallery directors, whose appreciation was far from tokenistic or pigeon-holing - Kiffy Rubbo at Ewing Gallery, Melbourne; Ann Lewis of Gallery A, Sydney and Christine Abrahams of Powell Street /Axiom Gallery, Melbourne. More recently the efforts of Charles Nodrum Gallery in Melbourne have been crucial to her current re-evaluation and continued presence in Australia.

Surprisingly, Lesley Dumbrell had not been included among the three (!) female artists included in The Field, the 1969 seminal exhibition of new abstraction in Australia at the National Gallery of Victoria. Although fresh out of art school, Dumbrell had already found her distinctive stylistic voice, producing mature purely abstract paintings (two of which are shown at the AGNSW - see below). Although Dumbrell had shown examples at a dual show at Sydney’s Bonython Galleries with her then-husband, Lenton Parr, this had unfortunately not been seen by John Stringer, The Field curator. Today, the artist is circumspect about this oversight, deciding it had given her instead the freedom and space to develop at her own pace, free from scrutiny.6 Thankfully, some measures were taken to rectify this oversight in 2018 when the NGV presented The Field Revisted, in celebration of the exhibition’s 50th anniversary - devoting an extra room alongside the central recreation to the display of works of Virginia Cuppaidge, Lesley Dumbrell and Margaret Worth.

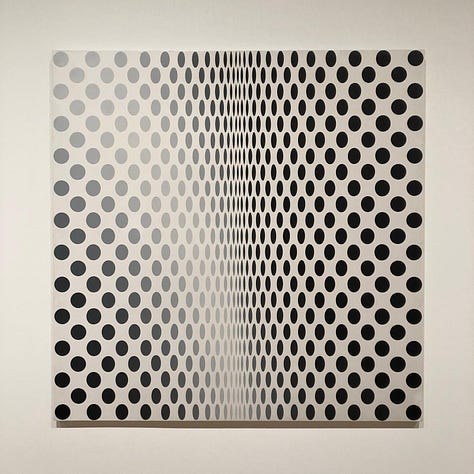

Employing a rigorous and mathematical style, Dumbrell can be cast as an Australian counterpart to pioneering British Op-Art abstractionist Bridget Riley, whose black and white print work Dumbrell saw in Melbourne at the Belvedere Op Art Exhibition in 1968 and knew “mostly from reproductions”7. The nascent Australian National Gallery (today the NGA) had already acquired two important colour paintings by Bridget Riley: Gamelan, 1970 purchased in 1971 and Veld, 1971, purchased in 1977, well before the gallery had a permanent exhibition space, and consequently, it appears these works were not exhibited in Australia until various touring exhibitions in 1978.8

The foundational fabric of Dumbrell’s work is the modernist grid, one that provides her with “a structure on which I can hang colour and play with it”.9 It is this repetition of an entirely abstract geometric patterning that elicits subjective and often disorienting optical phenomena in viewers. As Janine Burke rightly pointed out in 1990, optical effects in art “were conditioned by a taste and a style that were part and parcel of the 1960s”, referring to the ubiquity of printed optical effects à la Victor Vasarely in publishing, advertising and design throughout this decade.10 It was de rigeur to abandon the elitist status of the original work of art by mass-producing cheap screenprints, an impersonal medium that perfectly encapsulated the democratic and cosmopolitan developments of the era. Interestingly, Dumbrell did not ascribe to this ethos and created very few multiples of her works. Instead her unique and original paintings from the 1970s, polished and free of personal gesture, were still successful in harnessing the aesthetic zeitgeist and achieved popular dissemination purely by being included in representative collections and exhibitions.

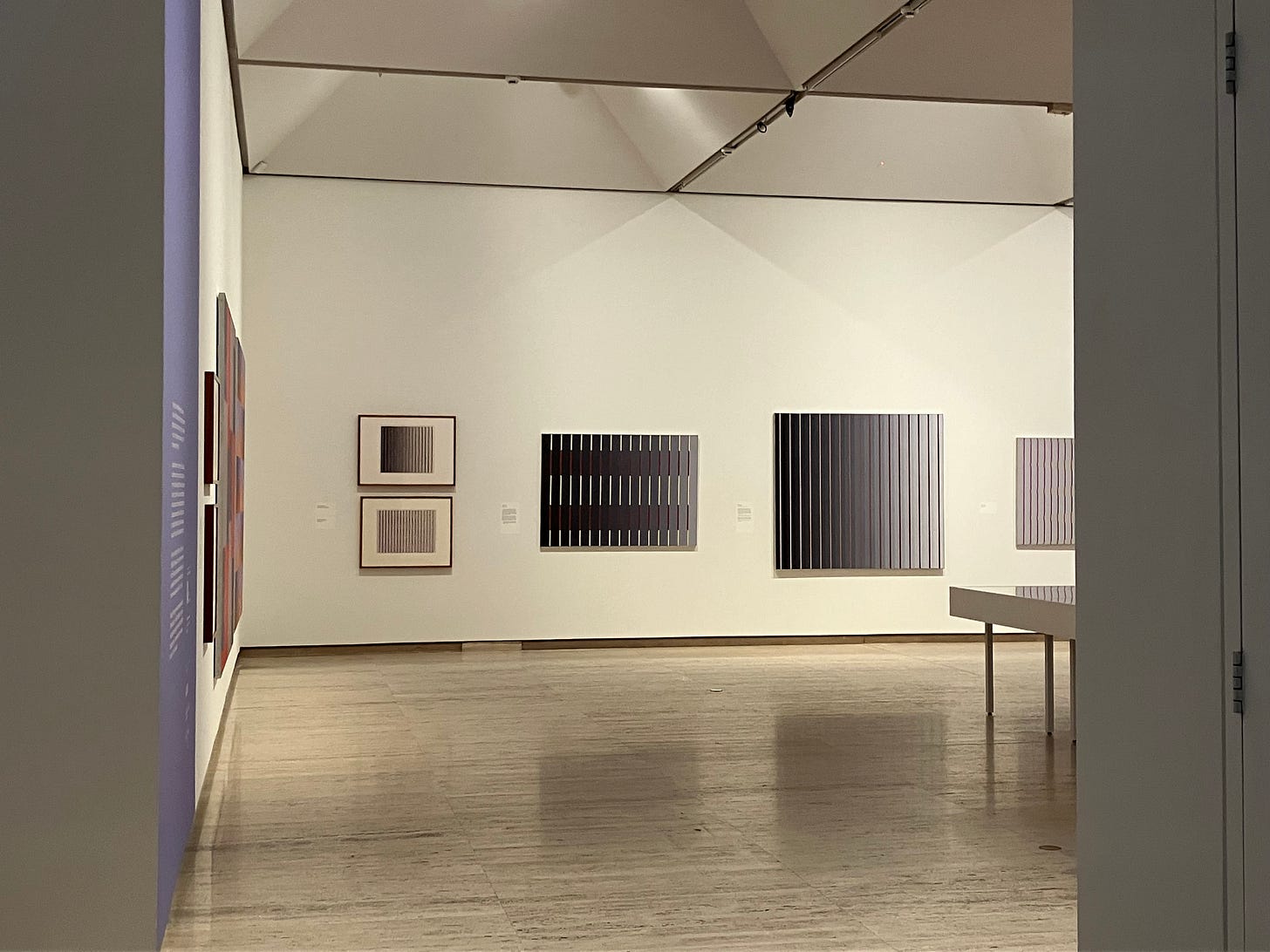

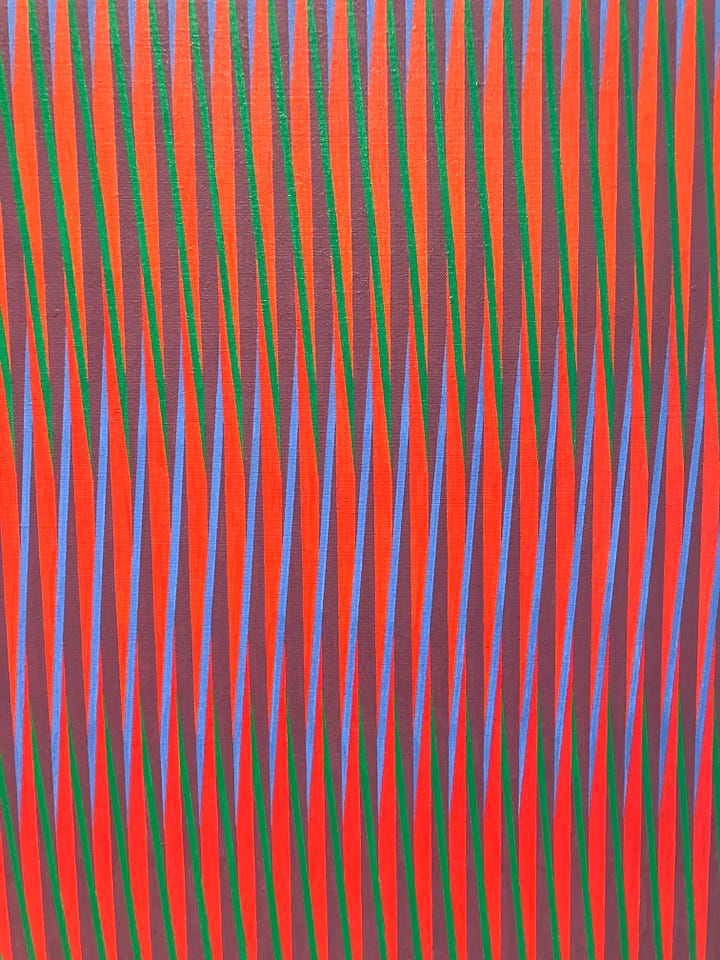

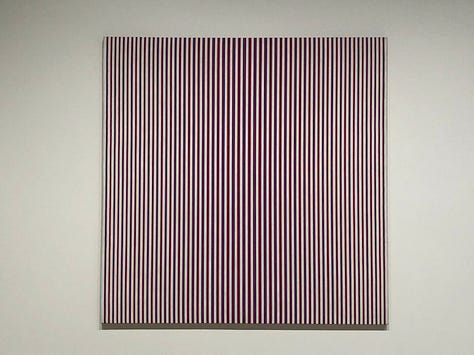

In contrast to Bridget Riley, whose works from the 1960s in black and white were well suited to printed reproduction, Dumbrell’s focus had always been on the relative effects of colour and their arrangements. Similarly, the creation of new fast-drying synthetic polymer paints such as Liquitex allowed Dumbrell to work with rich colour hues, sharply delineated and exact lines, flat surfaces without visible brushstrokes and fast progress in works of her preferred large formats. She wrote in an artist’s statement “My work has no direct political content, but clearly it must have a personal bias of some kind [...] colour is for me the strongest motivation, the way I try to convey emotion”.11 Unfortunately, her scintillating and at times raucous colour harmonies are not immediately evident at the entrance of the Art Gallery of New South Wales exhibition - from a distance, the striated works from the 1960s meld together to become a misleadingly dun, grey, combination. It is only once you’ve fully committed to entering the room that you are rewarded with the optical punch of her colours.

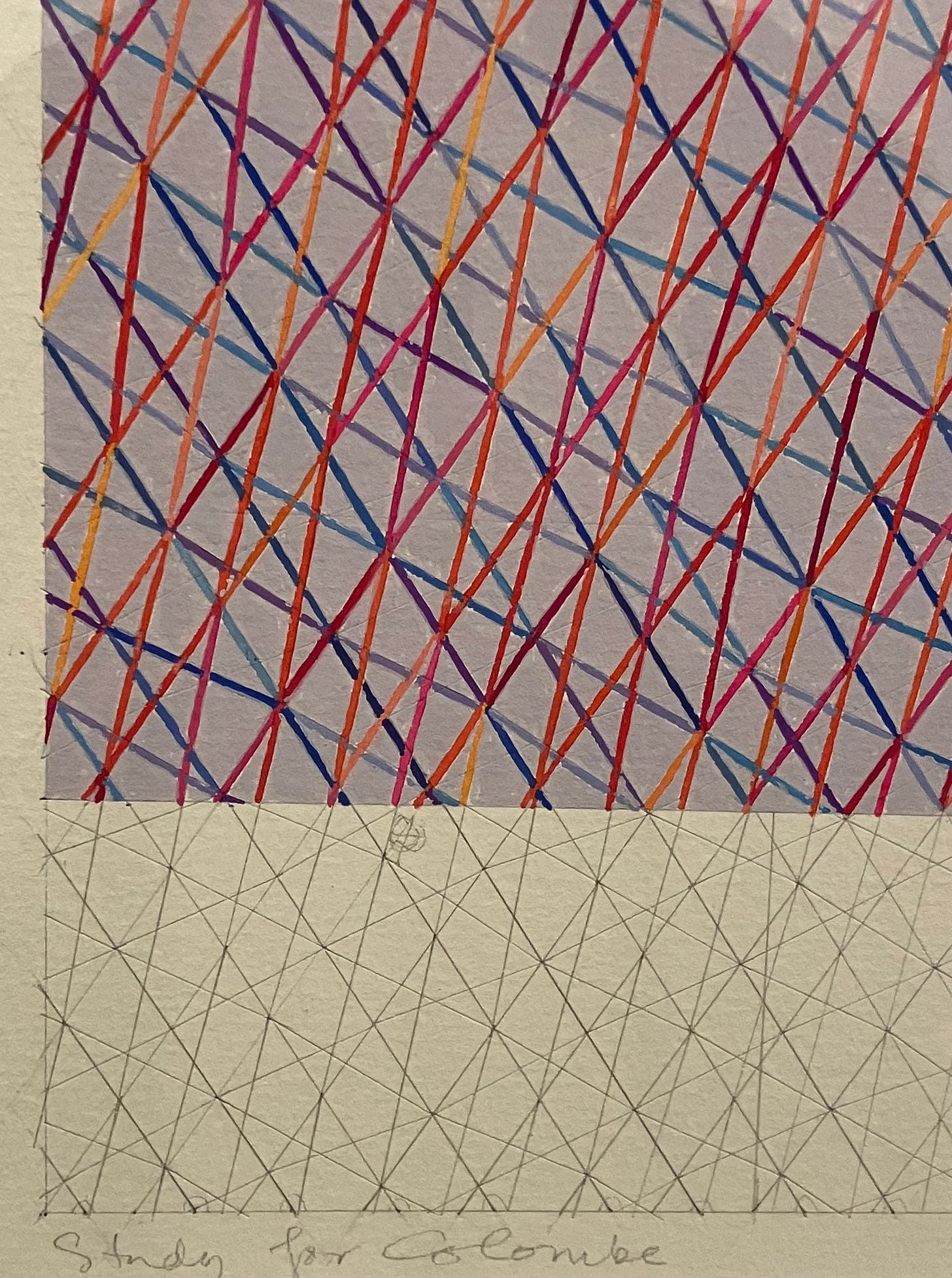

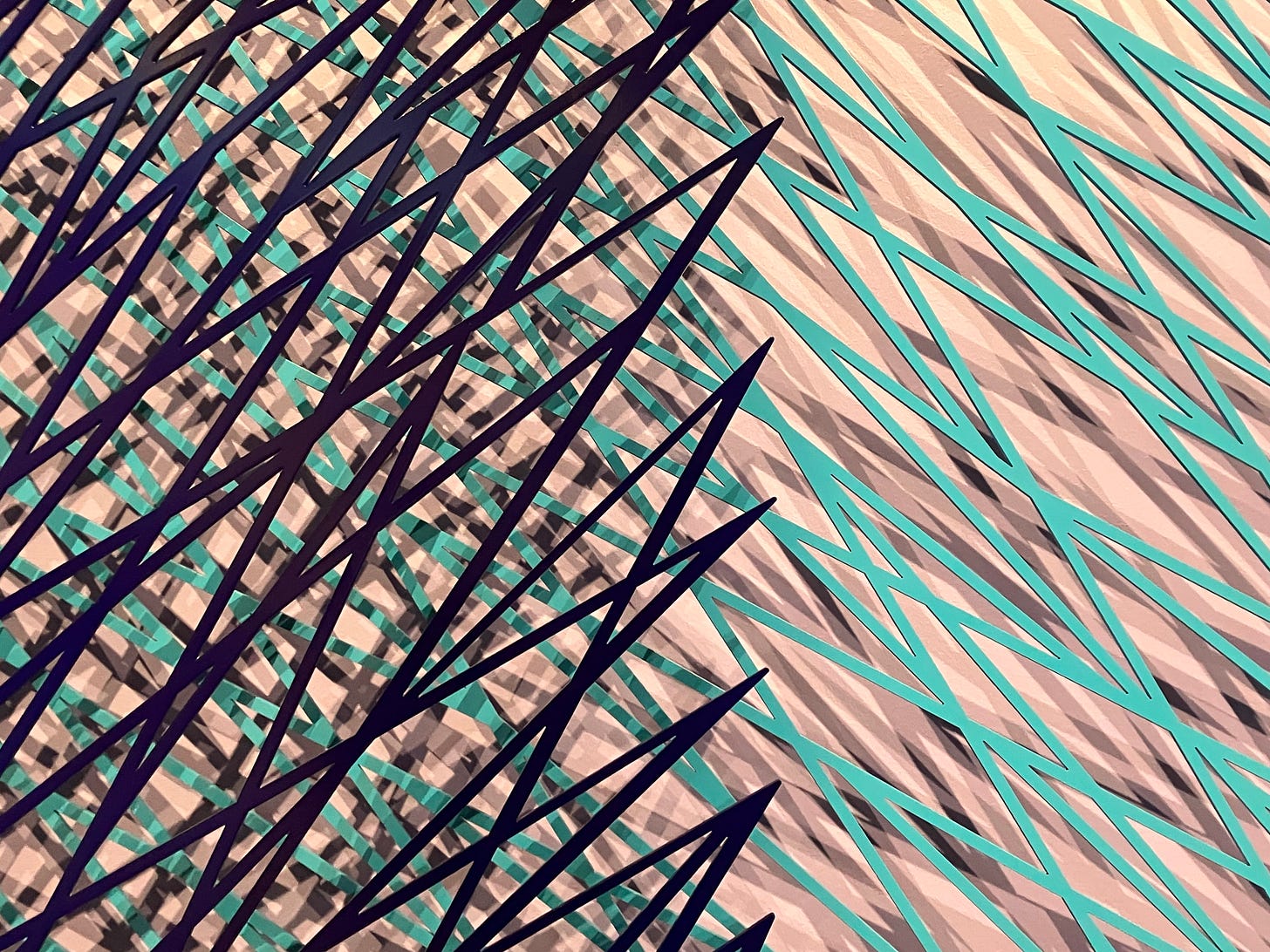

Dumbrell’s expertise in creating tightly woven patterns of slender stripes of colour is something to behold. Her subject matter is purely formal, and reliant on subjective associations to natural phenomena. Her titles provide little by the way of overt meaning, making only oblique suggestions as to their interpretation. In 1976, the Canberra Times reported that “all her [Dumbrell’s] paintings were preceded by detailed studies”. 12 Today, it is the presentation of these supporting works on paper that provides a personal depth and insight into the artist’s practice - a crucial peek behind the rigid curtain that the artist creates with grids and a ruler. The exploratory and unfinished works are captivating. They contradict the paintings, which are so slick and complex they have the appearance of having been generated, arriving fully-formed from thin air, all trace of human hands absent at least until your nose is on the surface. This clear presentation of the “hand-made” process behind each painting is revelatory and also serves to distinguish her work from those of Riley, which have all, since 1961, been executed by assistants.13 Thus, Dumbrell’s output has not been prolific throughout her career, her works are the result of slow consideration and meticulous construction. The arrangement of colour harmonies and relative densities of pattern conjures movement from static planes, symphony and cacophony from silence. However, having reached the zenith of this expression in the mid-1970s, Dumbrell had no choice but to change course in the subsequent decades. Her shallow painted surface morphed into looser, more organic arrangements with jagged contours in the 1980s, before returning to the geometric straight and narrow in the 2000s and 2010s.

Displayed at the front of the exhibition is Dumbrell’s most recent work, a surprising foray back into sculpture. A medium the artist had not attempted since early collaborations with Lenton Parr, Dumbrell has now discovered an ease of translation for her grids into three dimensions using the cutting-edge technology of laser perforation. The theatrical lighting of these superimposed grids is central to the artwork, for its generation of complex and intricate shadows (in much the same way as within works of fellow Australian sculptors Margel Hinder and Bronwyn Oliver).

Burke, J., Field of Vision: A decade of change. Women's art in the seventies, Viking, Penguin Books, Melbourne, 1990, p. 52

The artist, in conversation with Kelly Gellatly, Art Guide, Melbourne, Issue 150, July/August 2024, p. 75

Kudielka, R., ‘Introduction’, Bridget Riley. The Complete Paintings. Volume I 1959 - 1973, The Bridget Riley Art Foundation, Thames and Hudson, 2018, p. 7

The artist, in conversation with Kelly Gellatly, Art Guide, p. 73

Sturgeon, G., ‘Coarse but vital’, The Australian, Sydney, 18 December 1976, p. 25

Ryan, A. (ed.), Lesley Dumbrell, Thrum, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2024, p. 10

The artist, in conversation with Ryan, A., ibid, p. 51

In exhibitions Genesis of a Gallery, Part 2, 1978–1979, and Bridget Riley, Works, 1959–78, British Council Retrospective exhibition, respectively.

The artist, in conversation with Ryan, A., ibid, p. 53

Burke, J., ibid, p. 54

Artist’s Statement, in Burke, J., ibid, p. 37

‘Victorian Artist in Canberra for Opening’, Canberra Times, Canberra, 18 March 1976, p. 16

Bridget Riley. The Complete Paintings. Volume I 1959 - 1973, ibid, p. 15